~/Minimum Viable Programmer

14 April 2024

This is an extended, blog version of a talk that I’ve given at DDD Melbourne and that I can present to companies and clients.

Apart from the technical and consulting work I do with my clients at SixPivot I also manage a few internal projects, like mentoring and coaching our consultants around their professional development.

Professional development is something I’m passionate about. Not just “hey why don’t you take a day to learn Vue?” but at a deeper level - thinking about careers, interests, strengths, and helping to figure out areas for improvement.

I’m constantly learning new things, about our industry, my profession, and about myself.

The kind of work we do tends to encourage working long hours and learning in our own time.

I don’t think this is necessarily sustainable in the long term. Burn-out and mental health issues are pretty common in our profession.

So, when I’m working, I need to be careful about what I decide to do at any moment.

In this post I’ll go into some ideas and principles I’ve learned over my time as a developer, as a consultant, and as a leader. And hopefully I’ll also show how you can use these ideas and principles to help you make good decisions, both in your job and for yourself.

Themes

These are the themes I’ll cover:

- Last Responsible Moment,

- Cognitive biases,

- Investments,

- Risk, and

- Hustle vs sustainability

I’m a strong believer in the Last Responsible Moment principle. I’ll mention it a lot.

Cognitive biases and logical fallacies are behaviours that humans have evolved to form part of our decision making process. Being aware of them and recognise when you’re being influenced by one or more of them is a way to improve that process, in a world where we aren’t actively being hunted by large mammals.

Spending your time and effort is an investment. So I’ll cover cost-benefit analysis, and the sunk cost fallacy.

And I’ll talk about reducing your cognitive load, hustle culture, being sustainable throughout your career, and making good decisions for your project, your employer, and most importantly for yourself.

Baby developer Rebecca

My first real job in IT was building in-house systems for a small financial planning firm in Regional Queensland.

I was the only developer, and in fact the entire IT department. I was in that job for about eight years, so it is a pretty big chunk of my career so far.

Being in a small but growing business like this gave me exposure to working with management, end users, and clients. And I needed to learn how to make good, or often good enough decisions quickly.

I also worked very long hours, pulled overnighters, and work entire weekends, to implement and roll out new features, or to make big infrastructure changes as fast as possible, so my work didn’t get in the way of the rest of the company’s.

I regularly took work home with me, and spent most of my little “free” time learning and trying to “level up” as a programmer.

That job was an excellent learning experience, but it took a lot out of me.

Even though I was learning how to make good decisions for the business, I wasn’t applying that to my own life.

I think that understanding how we make decisions is essential in being able to improve those decisions, and learning how and where to apply those decision making skills is a way to improve our overall quality of life.

Last Responsible Moment

I’m going to introduce the Last Responsible Moment principle early in this post.

I use it every day for both big and small decisions. So I’m going to refer to it frequently.

Concurrent development makes it possible to delay commitment until the last responsible moment, that is, the moment at which failing to make a decision eliminates an important alternative.

Lean Software Development: An Agile Toolkit, by Mary and Tom Poppendieck (emphasis mine)

Basically, the principle is that we should avoid making a decision until the point where the cost of not making the decision is greater than the cost of making it.

Understanding how this works in practice is pretty important.

For me, this also means getting just enough information to make important decisions at the point where they have to be made.

See also the information bias, which I talk about later.

When I’ve got less information, I also like to make important decisions early, but in a way that later lets me change those decisions and shift direction without a huge cost.

Sunk cost fallacy

A sunk cost is something that has been spent and can’t be recovered.

“I paid $10,000 for these stocks. I can’t sell them for $5,000!”

(even though you could spend that $5000 on a better performing investment right now)

The sunk cost fallacy is the tendency for sunk costs - past decisions - to influence future decisions, by believing that the investment - the sunk cost - justifies future costs against that investment, and discounting the value of other possibilities.

AKA “throwing good money after bad.”

“A past team member wrote a key component in our system using Elixir. It’s buggy, the team member has moved on, and nobody knows enough Elixir to maintain it. This component is starting to become a liability.”

Once, I inherited a system that had a component a former team member had written in Elixir.

For context, we were a .NET shop and the rest of the system was written in C#, but the former team member really wanted to write the component in Elixir as a learning opportunity.

And then they left, probably to a job where they could write Elixir all day.

The component mostly worked, but there were edge cases with incoming data that caused some nasty bugs.

“We’re invested in using Elixir now, Employee X spent 5 weeks writing this component. We can’t just throw that work away.”

Not changing direction is actively making a decision to continue investing in the Elixir component.

You could identify two options at this point:

1 - Keep the component, learn Elixir, and take 4x time to fix the bugs and maintain the component,

Or,

2 - Throw away the five developer weeks you’ve invested, rewrite the component in C# (which the entire team is familiar with), and fix the bugs.

Option 1 is where sunk cost comes into play. You don’t want to throw away that work, so you invest more time and effort into fixing the bugs and maintaining the component that nobody really understands or even really wants to work on.

Maybe it gets to a point where people are quitting rather than having to deal with this painful component.

The bad investment has become an ongoing liability at this point.

Ignoring the sunk cost and going with option 2 is most likely better in the long run.

The rewritten component is easier and cheaper to maintain, and maybe the team will be happier when they need to work on it.

Understanding that we are biased towards over-valuing investments made in the past can help with making better future decisions.

This can apply to small decisions, too.

A professional poker player will set a “loss limit” - an amount of money that they’re prepared to lose.

That way, if they’re in a losing game, they’ve set a clear point where they can re-evaluate their position, and decide to “cut their losses”.

For a developer, this is like setting a time box.

You’re working on a feature, you have unknowns around the implementation, and you want to experiment with it.

So, you set a time box of, say, two hours, and then at the end of the two hours you stop work and assess where you’re at.

If it feels like you’re on the right path - you’re solving the unknowns, it seems like a good directions - then you can consolidate the work you’ve done, and keep going.

But, if it isn’t working out - there’s too much friction, you haven’t made sufficient progress and the unknowns are being solved - this is the time to cut your losses and find another solution.

Either way, you’re making a more informed decision without a big up-front cost.

Remember that just writing something off as a sunk cost might itself not be the best decision.

As developers, it’s easy to fall into the “rewrite all the things” trap.

3. Port the Elixir code to C#

Option 3 might be that some of the Elixir component can be recovered and reused during the pivot to C#.

And in fact that’s what I did. I took the Elixir code and ported it more or less directly to C#, and while I was doing this I wrote unit tests around the implementation and found and handled the edge cases that were causing bugs.

As it turned out this only took a couple of days.

Being agile means adapting to new conditions and taking advantage of the environment.

The sunk cost fallacy is the tendency for decisions that we’ve made and costs that we’ve incurred in the past to influence our future decisions, at the risk of making poor decisions.

Or, another way of putting it is that we over-value our past investments and decisions, and this adversely affects our future decisions.

Cost-benefit analysis

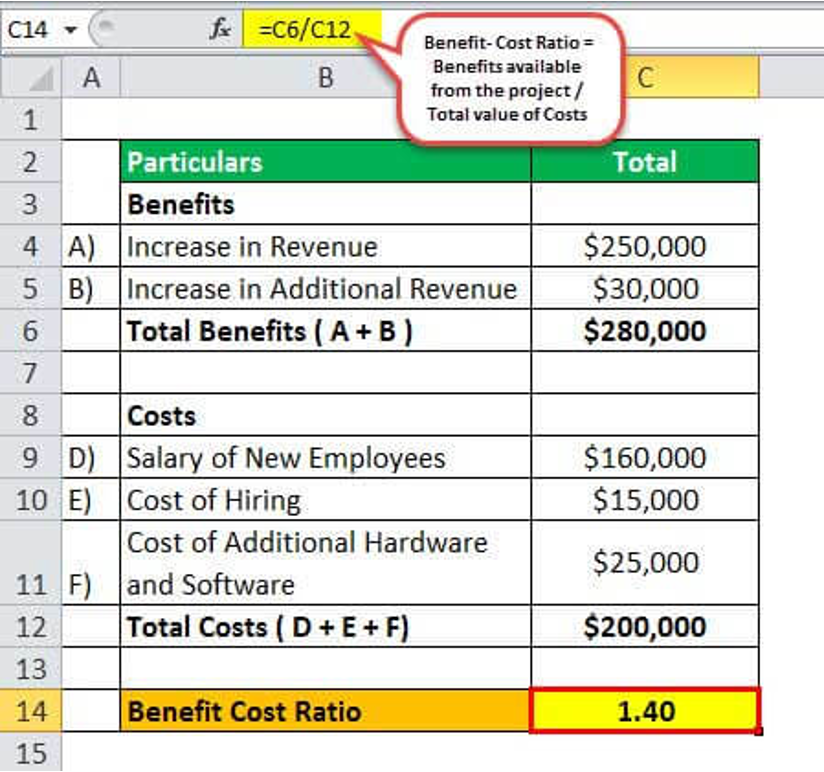

Cost-benefit analysis is where you work out the costs of doing something, you work out the benefits that you’ll get from doing it, and compare both sides to make a more informed decision.

This can be formalised, or it can just be a quick assessment in your head. A cost-benefit analysis is important when making good decisions.

Often we make decisions based on “intuition” or “gut feel”. This can be ok for some small decisions, or where you’ve solved similar problems before and know when to apply your experience.

Like, seeing an error in the browser console about a response not being able to be parsed. My experience tells me that 100% of the time this is because a server error is being returned and the client is trying to parse a HTML response as if it was JSON. My intuitive decision is to start by looking for the error being returned by the server, not dive into the code figure out where it’s being parsed.

These intuitive decisions are important, but a lot of our decisions need more effort as they do matter and directly affect our day, or our week.

In finance, a cost-benefit analysis is quantitative. You quantify each cost or benefit by giving it a numeric value - usually in financial terms like dollars.

This reduces the “human”, emotional element in decision making, which sounds horrible, but when you remember the cognitive biases that influence our automatic decision making process it can be quite useful.

I think there’s utility in qualitative cost-benefit analysis though.

Sometimes you can’t assign a number. Like, a cost that is “this would be boring”, or “this wouldn’t be fun”. For me these are still real costs.

I try not to worry too much about quantifying everything, but I find that a cost-benefit analysis can help with making decisions.

A while ago I needed to make a recommendation to a client about how to add a new filtering feature, and to give them enough information so that they could understand it, and so that the development team could estimate the effort needed to implement the new feature.

I wasn’t familiar with the code, or even really with the application itself. It was a complex screen - it summarised a lot of incoming data.

My first, intuitive thought was that I should dive into the UI and work my way down to the raw data, and map out the data flow, so that I could understand it end-to-end.

This felt like the right decision, because then I could figure out precisely how to build the feature.

But I realised this would take a very long time, and I felt it would be really boring and tedious, and not a great use of my time.

I needed to decide how to proceed - how I would spend the rest of the day. So, I did a mental cost-benefit analysis. Here’s how it looked in my mind, although with less unicorns and sparkly rainbows and more tables.

Full, deep analysis:

| Cost | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Lots of work | Full understanding of the application |

| Not very fun | Can give a detailed explanation of the implementation |

| Will take a long time | Very low risk for the eventual implementation |

Limited, high level analysis:

| Cost | Benefit |

|---|---|

| Higher risk when implementing | Fast |

| Doesn’t teach me details about the application | Don’t have to dive into lots of code |

| Can’t give a detailed explanation | I don’t have to understand the entire system |

| Leaves some questions unanswered | Provides the answers that are needed right now |

| Increased chance that I might be wrong |

Both options had legitimate costs and benefits, and it still wasn’t clear what was the best choice.

I realised that to choose, I needed to understand what’s important to me at this moment?

“Do I need to completely understand the application right now?”

If I don’t do that full analysis, I might make a mistake, or I might miss something.

Was that ok?

In this case, yes.

My client just wanted to know if the feature was possible, understand how it could be implemented, and get an informed estimate from the team.

Deciding to do the limited, high-level analysis meant that I could provide a recommendation in a few hours, rather than the three days that I figured a full analysis would take.

This is what I needed to understand:

- What data is coming in - inputs

- What we want to see - outputs

- What additional data we need to do the filtering

- Where the filtering needs to happen

My job at that time wasn’t to understand the application in detail.

I know what the outcome should be.

I just needed to know what data was coming in, what data we needed for the filtering, and roughly where in the code the filtering needed to happen.

Anything outside of that was irrelevant, an implementation detail.

In the end my client was happy and got back a few day’s budget that could be used to actually implement the feature.

Cost-benefit analysis is an approach to evaluating the pros and cons of a decision, by making a comparison of the costs and benefits of that decision.

It gives us a systematic framework to compare alternative decisions.

So, using a simple cost-benefit analysis helps us make better, more rational, more informed decisions that solve the problem at hand.

Asking good questions

To make good decisions, we need good information.

To get that information, we need to be able to ask good questions.

Step Zero: "Bring me your _finest_ subject matter experts!"

Step zero is understanding who to ask what. Spend some time up-front figuring out who those people are.

Whenever I join a project, one of the first things I do is note down the people that I should be talking to.

And talk to end users if you can get access to them. They can give you highly relevant information. Just don’t confuse them with the product owners - the ones that actually need to make product decisions.

Being able to make effective decisions as a developer sometimes means acting in the role of a business analyst. Don’t avoid putting yourself in situations where you can learn something that helps you make those decisions.

Even when you’re working with the best business analysts, UX designers, and product owners, it’s common to get work where not all of the information you need has been provided.

Even when your team is “doing Agile” and having effective backlog refinement sessions, typically not every detail is totally clear.

You’re going to need to make some decisions. And to do that responsibly, you need to ask questions.

Make sure you’re asking the right questions, and getting meaningful answers.

Understand the context.

A hospital is probably going to have very different needs to a supermarket.

A data entry form for a supermarket probably needs to be optimised for speed and ease of use.

But a data entry form for a hospital may need to intentionally slow down users to limit errors.

“Does this date field need the time?”

vs

“Can you explain to me what this date field is going to be used for?”

Understanding context helps you decide which questions to ask.

Guide the conversation, but try not to ask leading questions. Use open-ended questions and let people explain rather than tell.

“Does this date field need the time?” is very specific and is probably going to get a very concise answer.

“Can you explain what this date field is going to be used for?” is open-ended, and the answer might be more relevant and deeper.

Just asking the first question might miss some detail that could be important. Lacking that detail means that you might make poorer decisions and need to rework or revisit them later on, when the cost of fixing those decisions is greater.

“That field is to record the time we did the maintenance work.”

Clarify: “Is that the time you started the work, or when you finished it?”

Make sure you’re clarifying and asking follow-up questions, when you are not sure, and when you think that your client isn’t sure.

And be aware of the Information bias:

Information bias: The tendency to collect more information than is needed to make a decision.

Make sure you’re getting the right information at the right time.

Applying the Last Responsible Moment principle

The Last Responsible Moment principle is one of my favourite tools. I use it every day, for both big and small decisions.

Sometimes we’re operating on limited data. Remember that we’ve got those cognitive biases at play. You won’t always make the best decision the first time around.

So, try to design your day in a way that doesn’t stop you from changing course.

Ambiguity effect: tending towards a choice we’re more familiar with, even given a choice with a better outcome

Rather than going down a path just because it’s familiar, see if there’s a better path first.

Time-boxing an investigation or doing a technical spike can be a great way to explore a decision without fully committing to it, and lets you pivot to something else later if you find out that it’s the wrong decision.

Spending 90 minutes to experiment is a good investment if it lets you make a more informed decision about something critical to your larger goals.

Say you’re building a system and need to decide which database vendor to use. It would seem totally reasonable to say that this decision should be made early, because you’re probably going to need a database to start building the system.

Software engineering isn’t civil engineering, and not all decisions in software development need to be fixed engineering challenges.

What if, instead of committing to a specific vendor early in the project, you made an early but flexible decision.

So, you start development on the system as soon as possible, without worrying too much about your decision. But, you work in a way that has a low switching cost if you later decide to change the database vendor. By avoiding vendor specific features, or by using an abstraction like an ORM. Or by making good software design decisions, like separating the data layer from the business rules and UI.

That way, if you later need to change vendors, you don’t have a huge switching cost. You turn a large and difficult to change decision into two different decisions. One made early, which allows you to continue with your work, and one made later, when you’ve got more information and experience.

- Remember the Ambiguity effect

- Time-box investigations

- Set yourself up to pivot easily

- Seek feedback early

Not all of our decisions are going to be right, but if you make flexible decisions early, gather feedback, and make better, more informed decisions later, you lower the risk of committing to a bad decision early.

Breaking the rules

There are general rules and principles that we need to learn and understand as software development professionals.

SOLID principles

- Single Responsibility

- Open-closed

- Liskov Substitution

- Interface Segregation

- Dependency Inversion

When interviewing someone senior for a job I usually ask what they know about the SOLID principles. It’s a pretty good baseline for gauging their exposure to more advanced concepts in software development that I would expect at more senior levels.

We break these rules all the time though. Whenever we build a monolithic CustomerService class, we break every single SOLID principle.

- S: The module has multiple responsibilities

- O: It can’t be extended, only modified

- L: An implementation of a function in the module can’t be substituted for a different implementation

- I: Users of the module (i.e. consumers of the service class) have to rely on methods they don’t use

- D: You’re injecting a monolith, not inverting a dependency

We don’t break these rules because we’re lazy or bad programmers. I’ve worked on projects started by programmers I admire that use this pattern, and I’ve done it extensively myself.

We’re making a trade-off. We’re trading technical debt for velocity.

Getting stuff done sometimes involves cutting corners and making decisions and breaking the rules.

But if we don’t first understand the rules and why we’re breaking them, we can end up making poor decisions and doing less than our best work.

Recently I used what boiled down to a global variable to implement a health check.

Global variables have famously been “considered harmful” since 1973.

I’ve known this my entire career. But my “considered harmful” code let me avoid several SOLID principles, which I felt would have had a much more harmful effect on the code.

Knowing the basic rules and principles, and doing a simple cost-benefit analysis, let me quickly find a middle ground that was “good enough”.

Another important principle to understand and follow is the Rule of Three:

Three strikes and you refactor

Write something similar two times, and on the third time refactor it.

It’s surprising how often the second or third time is unique enough that you never actually end up de-duplicating and refactoring.

A related rule I follow is this:

“If you finesse, you end in a mess” - David French, my boss

My financial planner boss from many years ago taught me this rule, when I was just starting out as a developer. I’ve held it close, and use it every day.

We want to write beautiful, elegant, and highly finessed code, that works perfectly for the cases that we optimise it for, but as soon as we try to apply it to a new case that doesn’t quite fit, the elegance falls away.

Sometimes, the simpler the better.

Deferring learning

It’s practically impossible to just be aware of every new development in our industry.

We can’t possibly make every decision 100% effectively.

The trick I’ve been telling all along is that we don’t need to.

So, invest your time carefully.

“A monad is a monoid in the category of endofunctors, what’s the problem?” - James Iry

Learn about functional programming because it’s interesting, because it’s a tool that will help you write more expressive code, not because you’re feeling FOMO and like you’re a lesser person for using a for loop.

Learn on the job when you can.

I’ve you’ve got it, use paid professional time as much as possible.

Look for employers that provide professional development, because they value their employees and are investing in them.

If you take opportunities for professional development seriously, you’re investing in yourself and in your career, in a way that let you continue to live your life.

“It’s three AM and I feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface of hardware description languages. I’ve got to start work in six hours to write this web application, and I still don’t really understand what a React hook does. I forgot to take the garbage out. I need a shower.”

Deciding to learn something is an investment in your time and attention, so treat it like any other investment. That is, cost vs benefit, learn about opportunity cost.

Apply the Last Responsible Moment principle to your learning practice.

And remember the sunk cost fallacy when it comes to your learning practice and professional development. Quitting a bad choice is a good thing.

Hustle vs Sustainability

Maybe I’m telling you to be lazy and selfish when I tell you to make easier decisions and deferring learning.

There’s a lot of hustle in this job. We learn in our own time, we often work long hours, and put a lot of ourselves into the work that we do.

This is at a cost to our personal lives and our mental health.

Maybe some selfishness is appropriate.

Burn-out is a big problem in this profession.

I’ve burned out numerous times, always with serious personal consequences. I’ve needed to take extended leave, seek medical help, and even left jobs a couple of times as a result.

The job itself was only responsible for maybe 20% of that burn-out.

I put too much pressure on myself. My relationships, my mental health, and my safety suffered as a result.

Honestly, I still struggle, every day.

I’m not writing this post because I’ve solved all the problems I talk about. I’m writing about it because I want to continuously grow and get better at making decisions for myself, and sharing that helps me understand myself and my mind more.

While you’re learning to make good professional decisions throughout your day, try to make sure they’re also good personal decisions.